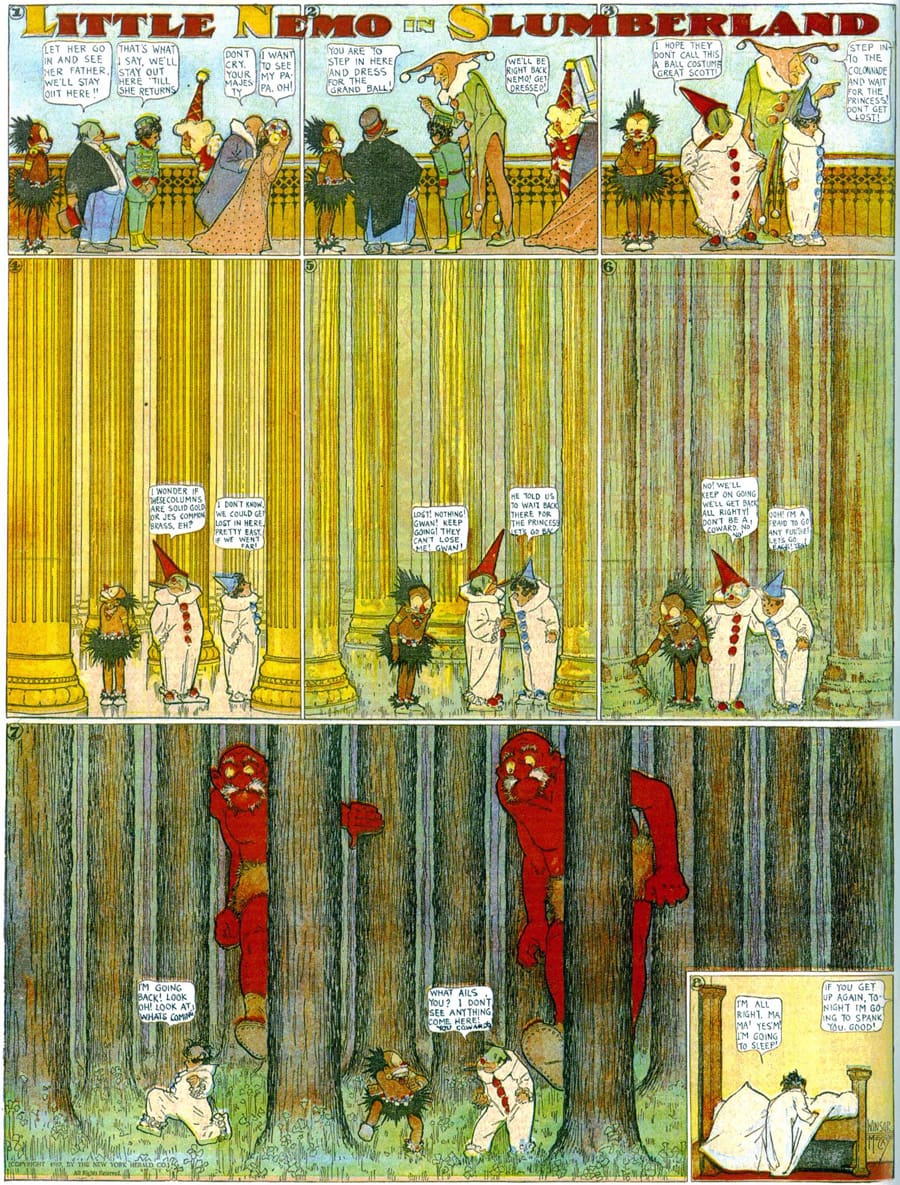

About 15 years ago, Torry Bend’s mother found a comic book at a garage sale and thought of her daughter, a theater designer who creates puppet shows. It was a compilation of the comic strip Little Nemo in Slumberland, by Winsor McCay, that ran in the New York Herald before World War I. The strip recounts the surreal adventures of a little boy whose nights on the town, or on the moon, or in some other ordinary or outlandish setting, always end with a rude awakening. Just as her mother expected, Bend was dazzled by McCay’s graphic virtuosity and couldn’t help imagining it on the puppet stage.

Last summer, Bend—now Associate Professor of the Practice of Theater Studies at Duke—was finally able to start working on a Little Nemo production. In the fall she called her informal company of puppeteers and assistants together, hoping to stage a piece at Manbites Dog Theater during its final year of operation—a stylish farewell to a much-loved institution. But it didn’t work out that way. McCay’s comic has a cast of characters fully representative of early twentieth-century American stereotypes, including Little Impie, a boy supposedly plucked from the African bush, with headlamp eyes, an apish mouth, and spiky tufts of black hair that match his spiky grass skirt.

Little Impie torpedoed Bend’s first attempt to realize the show at Manbites Dog. The script she’d written, which seemed fine in theory, was not fine in practice. “We pretty quickly realized that it had to be thrown out,” she says. “It just didn’t feel good. So then we tried to write something together as a community, and that didn’t work, either, because there was so much fear around using this material that it stopped the process.”

Although plans for a show at Manbites Dog had to be scrapped, Bend learned an important lesson: the thought of presenting a racist stereotype on stage can generate paralyzing fear in a theater group. She didn’t want to give up, and she didn’t want to sidestep McCay’s racism, but she realized that in order to do that, as a white woman, she needed a co-creator—a person of color who could check her blind spots. Bend approached Howard Craft, a prolific African-American playwright, poet, and educator based in Durham.

The thought of presenting a racist stereotype on stage can generate paralyzing fear in a theater group.

“He’s written plays that are basically superhero comics come to life,” says Bend. “He’s done a graphic novel. He had the perfect background for this kind of work.”

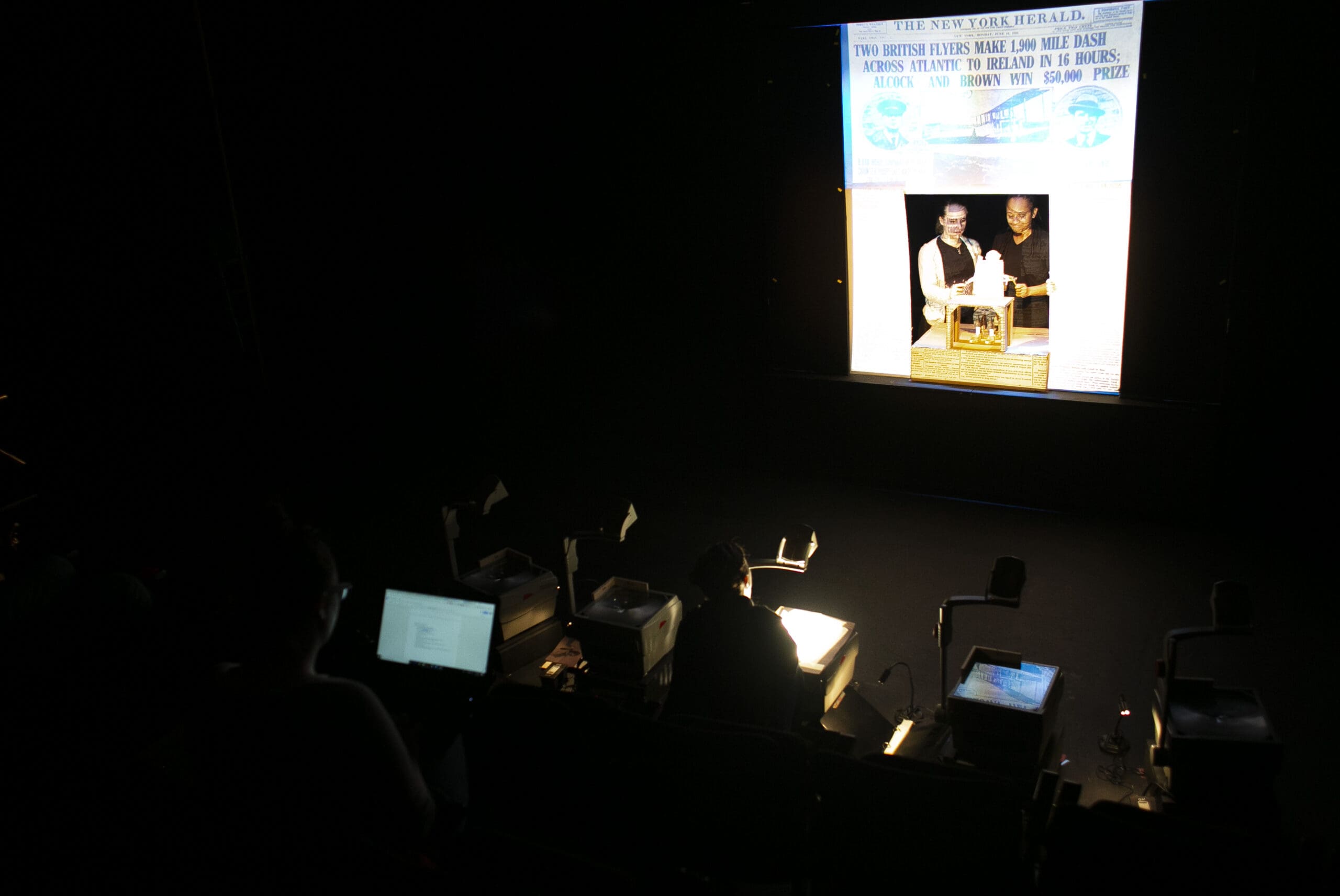

Not long after Craft joined the effort, Theater Studies chair Jeff Storer approached Bend with a surprising proposal. Plans for the spring Mainstage Production class had fallen through and he wanted her to take over the slot and lead a class that would develop and present Little Nemo as a faculty work in progress. She agreed to give it a try. Class registration was well underway when her course went on the books, but she was able to recruit a small group of committed students. She arranged for Craft to visit the class four times over the semester to work with students who wanted to try their hand at scriptwriting.

“I went in knowing that it was going to be an experiment,” Bend explained to the class, gathered for it’s final session to share pizza and analyze an intense but rewarding semester together. “We had no idea how it was going to work, and it was planned at the last minute so there was going to be some rough patches.”

By all accounts, the student writers felt a profound connection to Craft, partly because they started the semester in the same boat—trying to figure out how to adapt McCay for puppets and a contemporary audience. “They could bounce off ideas off each other and dialog in creation mode instead of teacher-student mode,” Bend says.

Or, as student Ashley Ericson put it, she could “sit down with Howard and be like, ‘this is what I’m thinking, help me.’ And he’d say, ‘ok, I think you’re losing that sense of agency—maybe you should think about doing it this way, instead.’”

Ericson says that Craft also helped her move beyond the obvious strategy of lifting stories from McCay’s strips to creating new stories using the characters and situations. “It was nice to have somebody break that barrier for us. He showed us that we could write whatever we want—as long as it’s somewhat related, it’s fine,” Ericson shared.

Craft’s focus was on writing, not on race. “They explored what they wanted to explore and came to their own conclusions,” he says. “All I did was to try to help them with structure, to make sure they were able to say what they wanted to say.”

To the students worried they might say something racist, Craft’s answer is matter-of-fact and non-judgmental: “Well, you probably are, but that’s ok. Racial bias is engrained in the society we come up in.” Furthermore, he explains, “We can’t learn if we fake something and we keep it to ourselves, because then we can’t bring it out, examine it, and see if it’s good or not.”

Only one student, Katelyn Gochenour, chose to engage head-on with Little Impie. She chose African American history as the focus of a research project that Bend assigned at the beginning of the semester. One of her main conclusions, she says, is that “writers like McKay have an important choice when it comes to representation, a choice that can either be right or wrong.” To highlight the consequences of his wrong choice, she wrote a scene in which a black Everyman sits at home, quietly reading his daily papers, until he’s confronted by McCay’s demeaning caricature. It was an exercise in pure empathy that’s striking in it’s simplicity, but according to Bend, it took a semester of intense effort and scrapped attempts to get there.

“That’s the power of choosing a historical topic [for creative work],” Craft says. It opens students’ eyes to things that easily slip by in a traditional history class. The simple fact that this blatantly racist cartoon was a routine feature of a mainstream New York paper can be a revelation, for instance. And Gochenour’s painstaking efforts led her to a realization of “what it would be like for a successful African American person living in, say, Harlem during this time to have to deal with everything that every other person has to deal with, plus this racist comic.”

Craft played a similar role in a freshman seminar at UNC-Chapel Hill in 2017. As part of his preparation to write the play Orange Light—about the 1991 fire at a chicken processing plant in Hamlet, NC, written for the Kenan Theater Company at UNC-Chapel Hill—Craft helped students in a freshman seminar write creative work based on their own research.

“In both situations,” Craft says, “the students seemed to get a lot out of it. As a playwright and an artist I got a lot out of it too. What can be more nurturing for you as an artist than to have 10 or 20-plus people all dealing with your idea and thinking it through?”

Craft is currently working to finish a script, entitled Dreaming: Little Nemo In Slumberland Revisited, so Bend can start storyboarding later in the summer. By November, they plan to have 20 minutes ready to show at La MaMa theater in New York City.

According to the official synopsis, Dreaming visits McCay’s characters 20 years after their creator’s death. “[They] revel in flashbacks to comic antics from their past. However, behind the remembrances, each has dealt with the repercussions of finding fame as a 2D stereotype. The impact of alienating their communities has taken its toll. As McCay is lauded in death for his influence, those who served in his art suffer from the weight of his impact.”

Even with little material from the class filtering into the final show, the students—as well as Craft and Bend—had a remarkable opportunity to face a difficult and frightening problem head-on, together.