Imani Mosley is a musicologist and bassoonist who just finished Duke’s PhD program in musicology. Born in Brooklyn but raised in Raleigh, she started playing bassoon in middle school, and continued at Enloe High School, Raleigh’s arts magnet, where she studied with the principal bassoonist of the North Carolina Symphony and was a band geek and history buff. She started college close to home, at Appalachian State, but transferred to Queens College, City University of New York, after her first year. Next came graduate work at Peabody Conservatory (technically, Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University), which she left with twin master’s degrees in bassoon performance and musicology. She started her doctoral studies at Columbia then switched to Duke, where she focused on the music of Benjamin Britten, advised by Phillip Rupprecht. Her dissertation is titled “‘The queer things he said’: British Identity, Social History, and Press Reception of Benjamin Britten’s Postwar Operas.” Her scholarship also encompasses contemporary opera, feminist and queer theory, masculinities studies, reception history, and British and American music from 1890 to 1945.

Mosley is an active and engaging presence on social media. In fact, as she says below, that engagement has led to many other things, like invitations to panels and interviews—this one is a case in point. Even on a platform of constant digital reinvention, she makes a wonderful case for passionate, old-fashioned scholarship.

Mosley takes a subject that seems esoteric to most of the world and mines it with rigorous love for gems to polish and share with curious people, making their worlds a little richer in turn.

A: When I was at Queens College, I asked a professor for a letter of recommendation. He said no, I hadn’t had enough classes with him, but that another professor had been talking about me and I should go see her. When I went to her office, she told me I was meant to be a musicologist. I only had a vague idea of what a musicologist was, but as I was having the conversation, I realized that it was the sort of writing about music and thinking about music that I’d always been interested in—I just never knew what to call it.

It was in a twentieth-century music class with the same professor that I decided I wanted to be an opera scholar. I thought I hated opera at the time, that it was sappy and the stories were terrible. Then we watched Wozzeck, and that had a huge effect on me. I thought, “Why did no one tell me that this is also opera?” Opera is fascinating and bizarre and it speaks to people in different ways than other kinds of classical music.

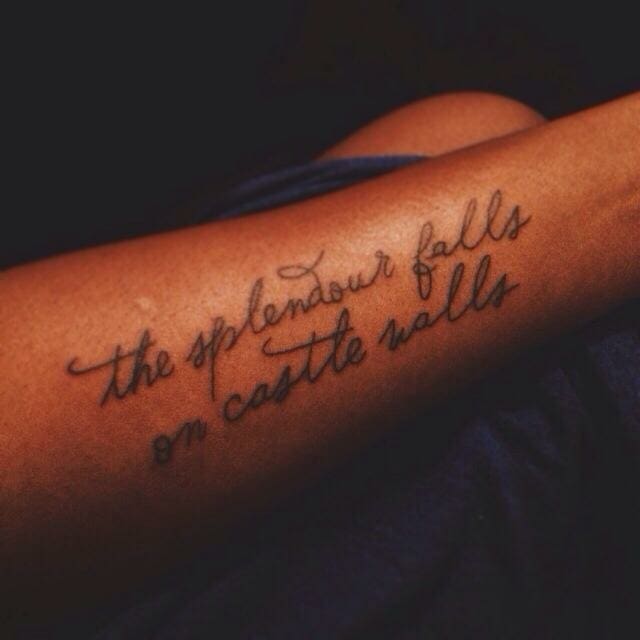

I checked out a CD of chamber music for french horn because I was writing a comparative analysis paper, to hear the works I was analyzing. I was listening through the whole thing and Britten’s Serenade for Tenor Horn and Strings came on. I was transfixed. I had never heard music like that before, had never heard English sound like that.

After that, I was at a bookstore and found a Britten biography for $5 and thought, “How perfect.” I read it with such a ferocity and tenaciousness. It felt like I’d found a kindred spirit. The moment was so powerful that I got it tattooed on my arm. I never want to lose the sense of what that experience was for me, and how it completely changed my life.

Yes. Thankfully, those voices have not been in Britten scholarship, where I have been welcomed with open arms from the beginning. Same with the wider community of medievalists and Victorianists and others who work on the British Isles. I’m very thankful for that.

But there is this idea that a black musicologist should work on black music. I remember once confronting a little bit of my own hangups about that at a conference many years ago. I was introduced to another black female musicologist and found out she works on 14th-century France. I remember thinking, ‘Oh, that’s unexpected!’

For musicologists of color, there’s a lot of hand wringing. We want to advance the scholarship on the musics of our communities. I have friends who have transitioned into that lane. A lot of us, including me, do a combination—I write a lot about 21st-century pop music and social issues. But those conversations are best handled internally—we don’t need anyone else to tell us what kind of music we should be working on based on how we look or where we come from.

“We don’t need anyone else to tell us what kind of music we should be working on based on how we look or where we come from.”

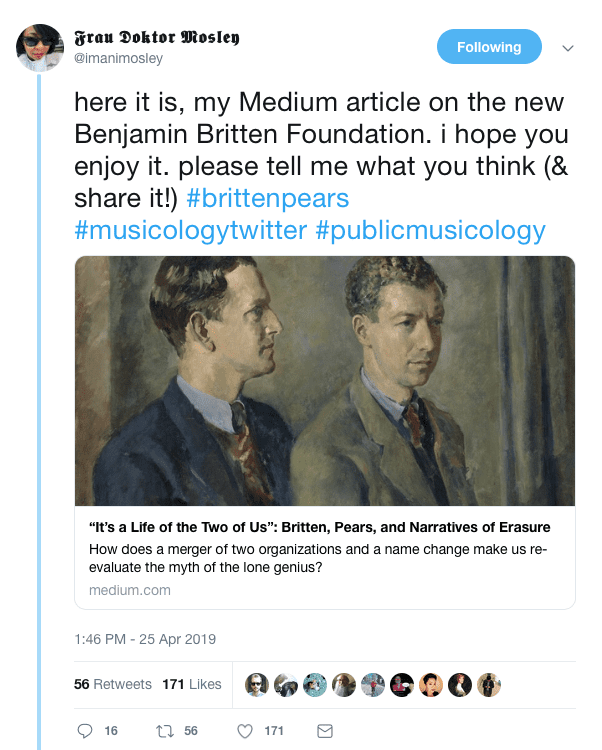

A: Sure. I think it’s being comfortable with complicated-ness. So, I just wrote a long-form article a couple of weeks ago on Medium about the changing of the Britten-Pears Foundation.

Q: I saw that—a real tempest in a teapot! We better set this up, though. The Britten-Pears Foundation was created by the composer and his life partner, singer Peter Pears, and it manages their house as a kind of museum and archive…

A: …yes, the Red House, in Suffolk…

Q: …and that’s going to merge with a music venue that sounds Hogwarts-y…

A: …Snape Maltings, home of the Aldeburgh Festival, a summer music festival started by Britten in the 1940s.

Q: And the plan was to drop Pears from the name of the combined organization.

A: Right. Instead of two sister organizations, it was going to be one thing—the Benjamin Britten Foundation. I think people were rightly upset. But they were saying that this is homophobic or it’s queer erasure, and that didn’t make a lot of sense to me. The idea that anyone who works at the Britten-Pears Foundation or Snape would be homophobic is wild to me. And can someone really be a victim of queer erasure when there’s a double portrait of them in the National Portrait Gallery? That’s a hard sell.

The thing about Britten is that he was never working alone. He thought collaboratively. Everything he wrote was for a person, for their voice, their style, the way they played their instrument. The best example of that is Pears. Yes, they were lovers and life partners, and that’s important. But they were also artistic partners, and that’s what really matters here.

Removing Pears’ name removes the thing about Britten that was at the core of his being as a creator. And that’s what keeps Britten from being put into the canonical genius box.

Q: You don’t want people to see Britten as just another heroic bust gathering dust on the piano?

A: Yes. And I wanted them to see that the issue is more complicated and nuanced than they thought. Fortunately, the foundation has decided to put Pears’ name back in.

A: I am. I was an early adopter. I celebrated my 12th anniversary on Twitter today.

Q: I saw that! Are you surprised it’s become this big?

A: No, I had a feeling in my gut that it was going to be a huge. Although, when I look back at my tweets from 2007, I think, ‘What was I even using this for?’

Q: It took time to figure out what you should actually tweet about?

A: Yes. But the turning point for me was when I created a Twitter account for Peabody. I tweeted everything that happened at the conservatory, which is a lot. Finally there was a way to let people know about all the things we were doing. Before long, I had thousands of followers. It was the third most followed Johns Hopkins account, after Hopkins proper and Hopkins athletics.

I remember talking with a lot of tech people at the time, being part of a Hopkins social media conference, seeing other universities and departments getting onto Twitter. And then, musicology Twitter was created—don’t know when, don’t know how…

Q: …but you’re a founder, and a stalwart.

A: Yes, I’m one of the heads of that movement, which is mind-blowing. I was actually cautioned by some older professors not to share too much about my scholarship online. But in being open about what I was working on and my struggles and all that, not only did I find/create this community, I became a better musicologist.

In part, it’s just doing simple things, like asking, ‘Hey, musicology twitter, where can I find this?’ The question spreads and people are out there trying to help. I try to pay that forward, when I see people asking for things—even if I can’t help I know that because my audience is so large I can retweet and someone else will likely step up.

People are engaging with me and my scholarship, and reaching out to me for interviews and work, because of the things that I write on Twitter. I spoke at Oberlin earlier this year, on a panel on public musicology and public music. Because, apparently, I am what passes for a young public intellectual now. That would have never happened if I hadn’t dove headfirst into social media.