Last fall, Duke alumni Alex Sanchez Bressler ’18 and Daniela Saucedo ‘18, along with Saucedo’s mother, Ana Brewton, started a fused glass business. The trio now melts glass at a sweltering 1480 degrees Fahrenheit in the Sonoran Desert. Their kiln—a one-ton oven consuming a quarter of the garage—completes one firing over the course of fifteen hours. This was not something they planned to do together.

La Colombe Contemporary Glasswork was launched during the COVID-19 pandemic within the confines of Brewton’s house in Tucson, Arizona. This surprise start-up combines Brewton and Sanchez Bressler’s love of glass art with Saucedo’s economics degree, and its story is one of making the most of changing plans and love for family.

Sanchez Bressler and Saucedo decided to leave Washington, D.C., when the pandemic hit. “A small apartment in a city with a high cost of living didn’t make sense for quarantine,” Saucedo said.

They packed up their one bedroom and drove cross-country to Tucson, Arizona, to move in with Saucedo’s family. There, Sanchez Bressler found work drawing on the skills he picked up during his time at Duke Arts as arts administration fellow, including graphic and web design. But what he was really interested in was the fused glass artwork by Saucedo’s mother scattered around the house.

“Never have I met someone with such a natural ability to understand proportion and color, who sees designs that make sense and sell quickly, but also look contemporary and beautiful,” Sanchez Bressler said. “She’s got it. And that, to me, was so exciting to see. It blew my mind.”

Sanchez Bressler was already familiar with glass. As a 2016 recipient of Duke’s Benenson Awards in the Arts, he used his funding to interview local farmers. He learned how to make stained glass pieces in creative response to their conversations.

“Never have I met someone with such a natural ability to understand proportion and color, who sees designs that make sense and sell quickly, but also look contemporary and beautiful.”

“I would spend eight hours a day just sitting with glass, which is almost like a religious experience,” he said. “You get to know glass and how it works—how it can hurt you, but also how it can be such a beautiful thing at the same time.”

That reverence for the practice stuck with him, so much so that when Brewton introduced him to fused glass—the technique of joining two or more pieces of glass by heat in a kiln—she opened up a whole new world of possibilities.

Spurred by a lifelong fascination with art and the sheer volume of creatives living in Tucson, Ana Brewton began her journey with glass twelve years ago. She started with lampworking, a type of glasswork in which a torch is used to melt glass that is then typically shaped into beads, but quickly found its limitations unsatisfying.

When Saucedo moved abroad for the Duke in Paris program, Brewton seized an opportunity to visit her daughter, hoping that she could rekindle her love of glasswork. They traveled to Murano, Italy, a Venetian island famous for its glass artworks.

“My mom walked around and was like, ‘Wait a second. I can do all of this,’” Saucedo said.

“That was an experience that really pushed me, because I saw the opportunities,” Brewton added. “I saw what I could do with glass, and it was beautiful.”

Back home, Brewton was able to get her hands on two kilns, and when she found that they were too small for lampworking, she decided to finally try her hand at fused glass. She attended one class around two years ago, and from there, she took off.

After Saucedo moved to Tucson and saw how much Brewton and Sanchez Bressler enjoyed working together on glass projects, she decided it was finally time to turn her mother’s desire to live off of her art into a reality.

“My mom has expressed multiple times that her dream is to live off of glass and be able to do that full time,” Saucedo said. “I take that very seriously. As an immigrant from Mexico to the United States, life has been hard for her, and she works so much and has very little time to devote to her craft. So, I said, ‘Okay, you want to make this happen? We’re going to make this happen.’”

Armed with Saucedo’s background in finance, Sanchez Bressler’s marketing savvy, and a brand-new kiln, a company was born: La Colombe Contemporary Glasswork. The name refers to the bottomless palomas the trio drank at a wedding in Mexico, translated into French to represent the family’s ties to their shared experiences abroad.

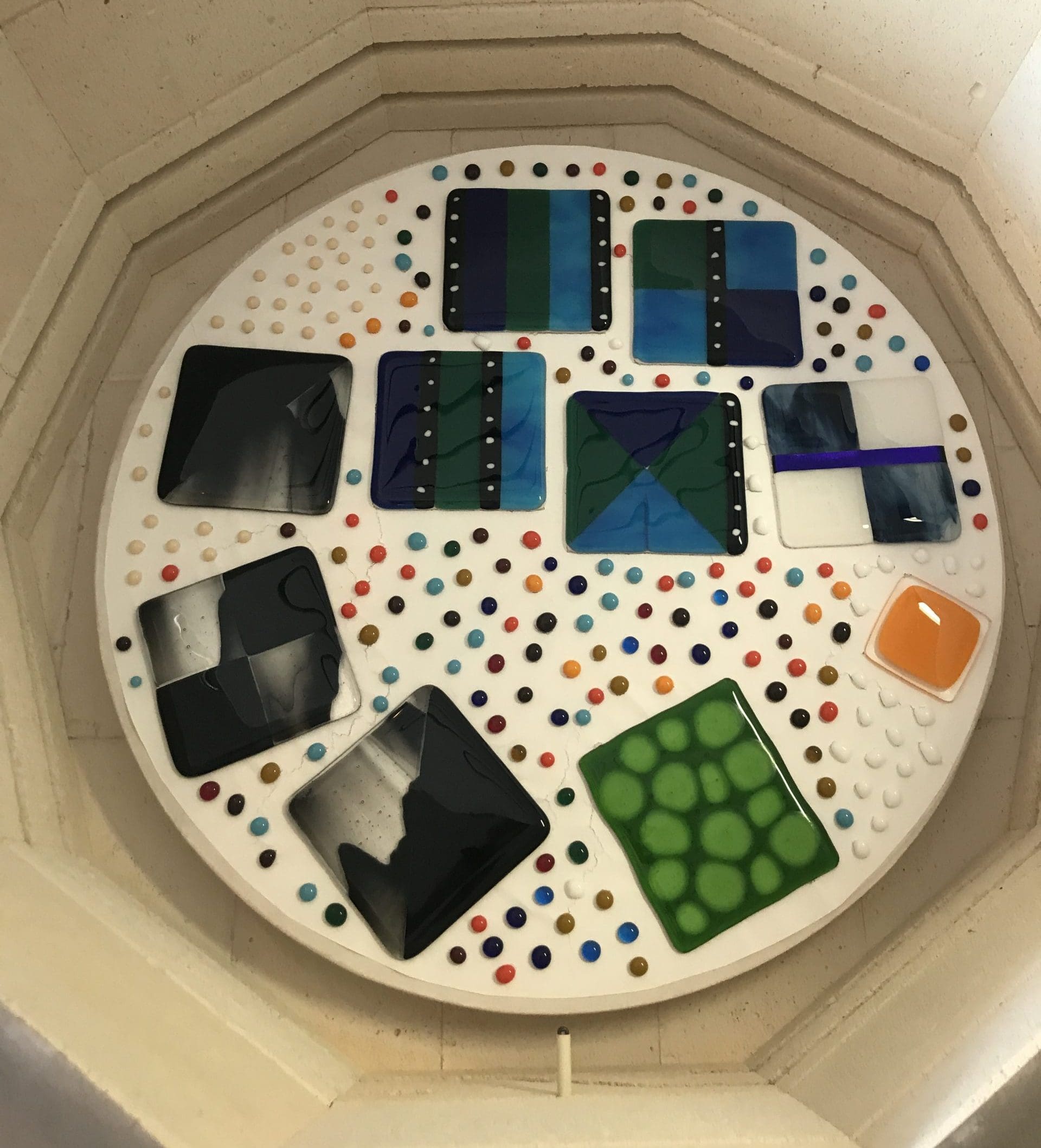

“It’s a completely in-house operation, which has been a lot of fun,” Sanchez Bressler said. “The kiln takes up a quarter of the entire garage, our photos are taken in a cardboard box with two trash bags taped to the side, and we cut glass on the kitchen counter.”

“I saw what I could do with glass, and it was beautiful.”

The process for making a new piece of glass begins in the night, while Brewton sleeps.

“Every piece I make comes to me in a dream,” Brewton said. “It takes me about three nights of dreaming to get to a final design, because I see it. Even when we get commissions, they don’t give us a picture—they just tell us what they would like, and I go from there.”

After Brewton and Sanchez Bressler finalize a design, they get to work on firing, fusing, and molding the glass—a delicate, painstaking procedure that can take upward of 50 hours for a piece the size of your palm. So far, La Colombe has taken commissions for everything from coasters and soap dishes to ornaments and spoon rests, in addition to their original designs.

As for the future of La Colombe?

“The goal is that in three years, I’ll just be doing this,” Brewton said. “I work in hospice care, and at some point, I’m not going to be able to keep doing that—it’s hard work. Glass is something I can do until I can’t hold the glass cutter anymore.”

Nina Wilder is a 2020 Duke English graduate from Raleigh, N.C. and this year’s arts administration fellow at Duke Arts. As a student, Nina was the editor of The Chronicle’s arts & culture section, Recess.