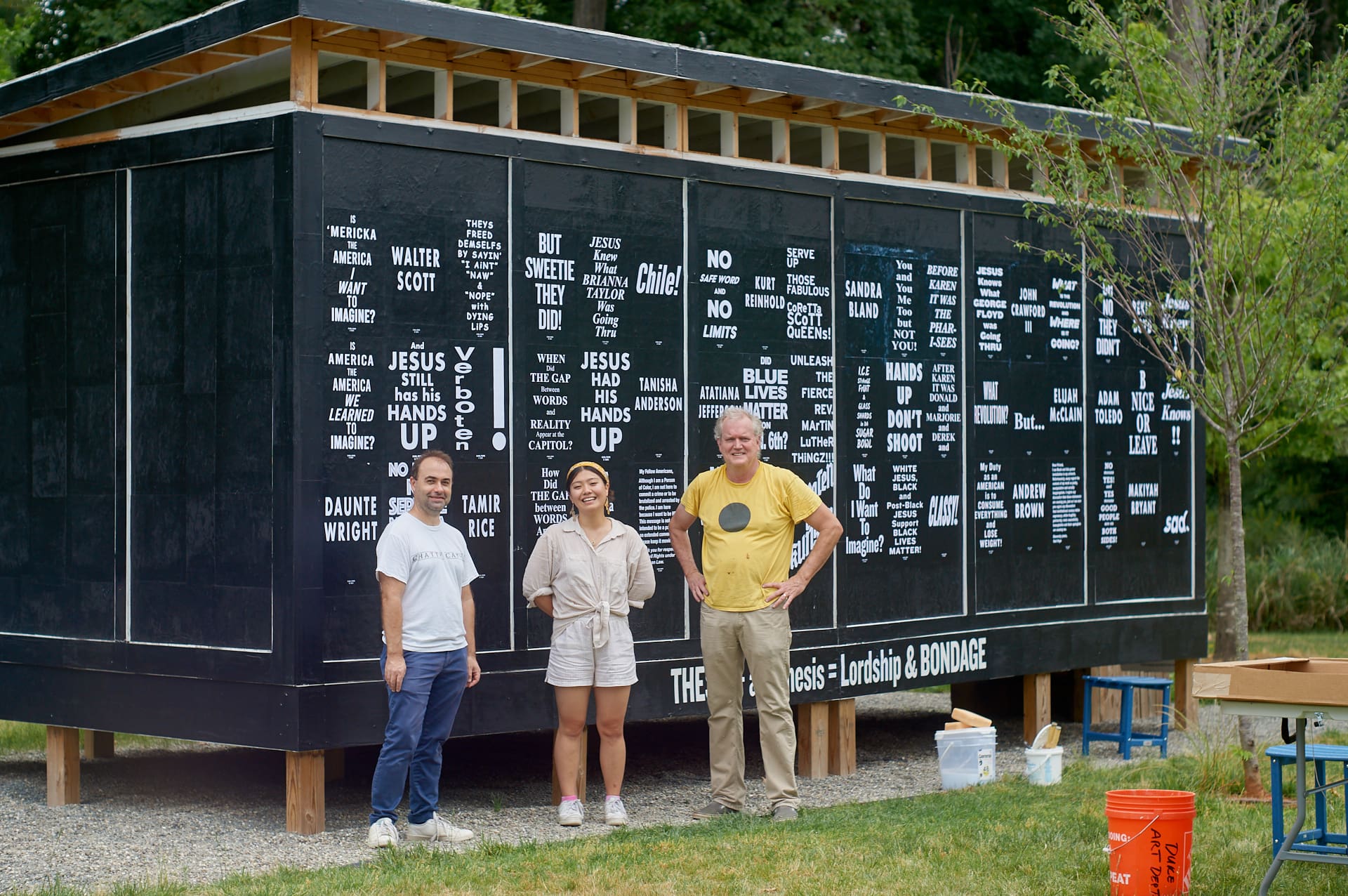

Visiting artist Carl Pope describes his ongoing graphic essay/poster installation “The Bad Air Smelled of Roses” (2004—) as “an attempt to use the advertising style of slogans to create epiphanies about the ubiquitous presence and function of Blackness within society, Nature, and the imagination of the viewer.”

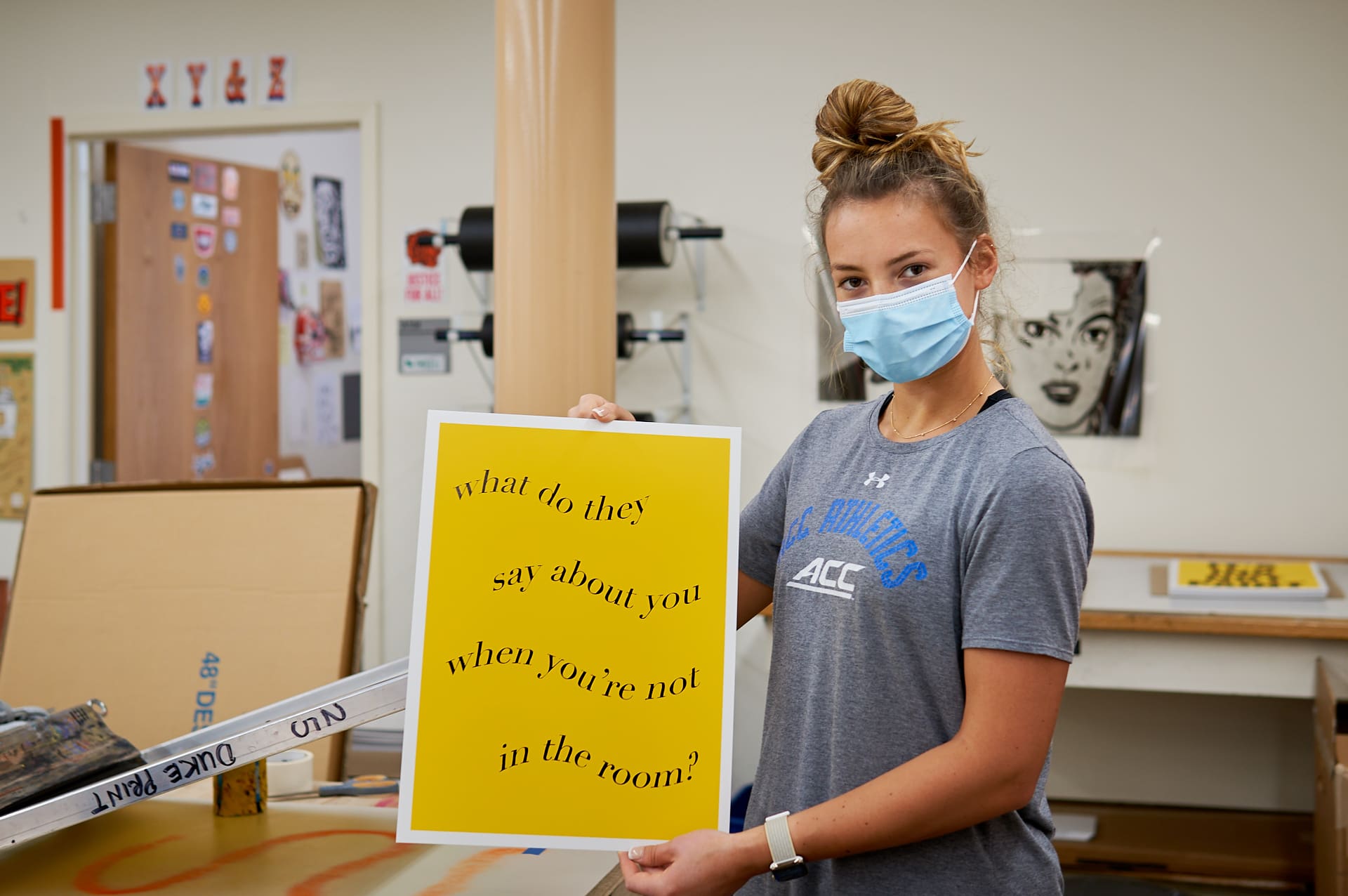

For this iteration of “The Bad Air…” at Duke University, Pope collaborated with students in “Poster Design and Printing,” taught by lecturing fellow and printmaker Bill Fick, with support from the Department of Art, Art History & Visual Studies and Duke Arts. Pope created 57 new slogans for the students to work with. The resulting silk screen and wheat paste installation is on view at the Rubix until December 1.

Creative Arts Student Team (CAST) member Dani Yan ‘22 spoke to Pope about his interest in bringing “The Bad Air…” to Duke’s campus, what it means to inspire “uncomfortable thinking” through art, and his ever-growing perception of Blackness.

After you spoke at Pedro Lasch’s Social Practice Lab, Professor Bill Fick was eager to get you more involved with the arts at Duke. What convinced you to come on board as a virtual visiting artist and to engage students with your “The Bad Air Smelled of Roses” project?

After my talk with Pedro Lasch, Bill Fick was very interested in producing a new installation with me, and when he showed me the Rubix, I got excited! The Rubix is not a traditional exhibition space with a specific audience, and it is within these types of exhibition spaces that artists are investigating public art and social practice strategies. The cascading effects of the pandemic have caused many changes across the production and exhibition of contemporary art, and creating exhibitions online or outdoors in unconventional locations is now necessary to reach and expand art audiences.

Working with Bill and sharing my ideas with Pedro and Duke students is a great opportunity to offer my particular perspective on public art and social engagement. My work in public art goes back to the mid-1990s, and most people are unfamiliar with what I’ve done, so it’s great for me to contribute my two cents to younger artists.

You’ve talked about how your high school photography teacher taught you that art could be a tool for social change. Now, you are in a quasi-teaching role. What do you think the students in Professor Fick’s class have learned from you? What would you like for them to take away from working on your project?

I think that the teacher/student dynamic is not really applicable in my work with students, since I am collaborating with them on the Rubix installation. I consider my artist residency at Duke an educational opportunity for me to learn, share, and collaborate. Because the social transformation we are experiencing in American society is an educational moment, where we are all teachers and students who can teach and learn from each other, there is much for me to receive from the students I’m working with.

In the Information Age, all fields of knowledge are transformed into one unified field, strengthened and expanded through writing. That unified field is also strengthened and expanded when binary oppressions, hierarchies, and social conventions are collapsed and reframed in service of the progressive, humane, and moral evolution of global contemporary society. The production of art and culture in the Information Age is the arena where we all individually and collectively participate (or not) in our human evolutionary process.

This is what I learned after exploring the idea of art as a catalyst for social change for 45 years and this, in a nutshell, is what I am inviting the students to consider as they make choices in their own creative, evolutionary process. It’s a brave new world out there, and I am as unfamiliar with it as they are, but I am working to orient myself to it the best way I can by being as culturally literate as possible given my circumstances.

When speaking about “The Bad Air Smelled of Roses,” you’ve said that you want the posters to provoke “uncomfortable thinking” in viewers and thus lead to “new possibilities.” When students—who would otherwise be viewers—become creators of the work, how might their experiences with the posters change?

I am inviting students and viewers to think in uncomfortable ways. Right now, in mainstream media and with people in my personal life, the refusal to think beyond one’s preference and interests makes thinking beyond those parameters uncomfortable. I want to inspire the kind of uncomfortable thinking that will, perhaps, disrupt the self-involved thinking that produces the increase in anti-social behavior, mental illness, violence, and corruption eroding civil organized society. If we are indeed living in the Age of the Individual, as the famous French deconstructionist Jacques Derrida suggests, then individual choice has more of an effect in the world.

“I am inviting students and viewers to think in uncomfortable ways.”

In the history of the “New Genre Public Art,” my projects would be regarded as “public interventions.” The hope is always for the viewer to arrive at “new possibilities,” but the reality is that I am only presenting an opportunity for viewers to consider the choices that produce their views. What the viewer does is up to them.

“The Bad Air Smelled of Roses” began in 2004. How are the new slogans different from those that you created 16 years ago? Has the intended impact of the work shifted at all?

“The Bad Air…” is the name of the overall writing project which has three iterations: (1) the original letterpress poster project, (2) the work of Karen Pope and myself in the printed version of “The Appearance of Black Lives Matter” by Nicholas Mirzoeff and now, (3) the Rubix installation at Duke. The original letterpress project is an ongoing graphic essay and literary interface that endlessly maps Blackness as a unified field. Right now, there are 110 posters in that iteration. The book is a mediation on the Black Lives Matter movement using visual material across a variety of historical periods.

The Rubix installation also explores issues around Black Lives Matter, but uses intertextuality to look at recent issues relating to militarized policing, state power, and other challenges to human freedom. That story behind the repeating accounts we hear and/or read in the news about police brutality and mass incarceration of marginalized people is akin to the repetitious biblical accounts of Jesus’s arrest, torture, and cruxifixction by the Pharisees and the Romans.

The slogans in this iteration also refer to Duke’s location in the South, with references to vernacular signage, MLK, and liberation theology. I also fashion slogans that reference various subjects like history, philosophy, English, linguistics, and LGBTQ activism. The Rubix is basically a shed, an example of vernacular architecture, which makes it the perfect location for a public art intervention on campus. Because the slogans imply Duke’s location and its function as an educational institution, they resonate within the context and the audience in which they were made.

You’ve said that “The Bad Air Smelled of Roses” is meant to answer the question “What do I think of when I think of Blackness?” — did your own thoughts about Blackness change as you created the new slogans for this project?

Yes, producing this project continues to broaden my perspectives about the occult correspondences and expansive meaning of what Blackness is and the what it can possibly mean. This project brings into sharp relief the difference between how Blackness functions in the cosmos and how it is slandered in language and deployed in the production of Western culture as an imaginary abyss of everything that creates an endless array of primal fears. Blackness ain’t that…

Dani Yan is a rising senior at Duke University, where he is co-editor-in-chief of FORM Magazine and a double major in Public Policy and Art History.

Duke Students & Employees save more!