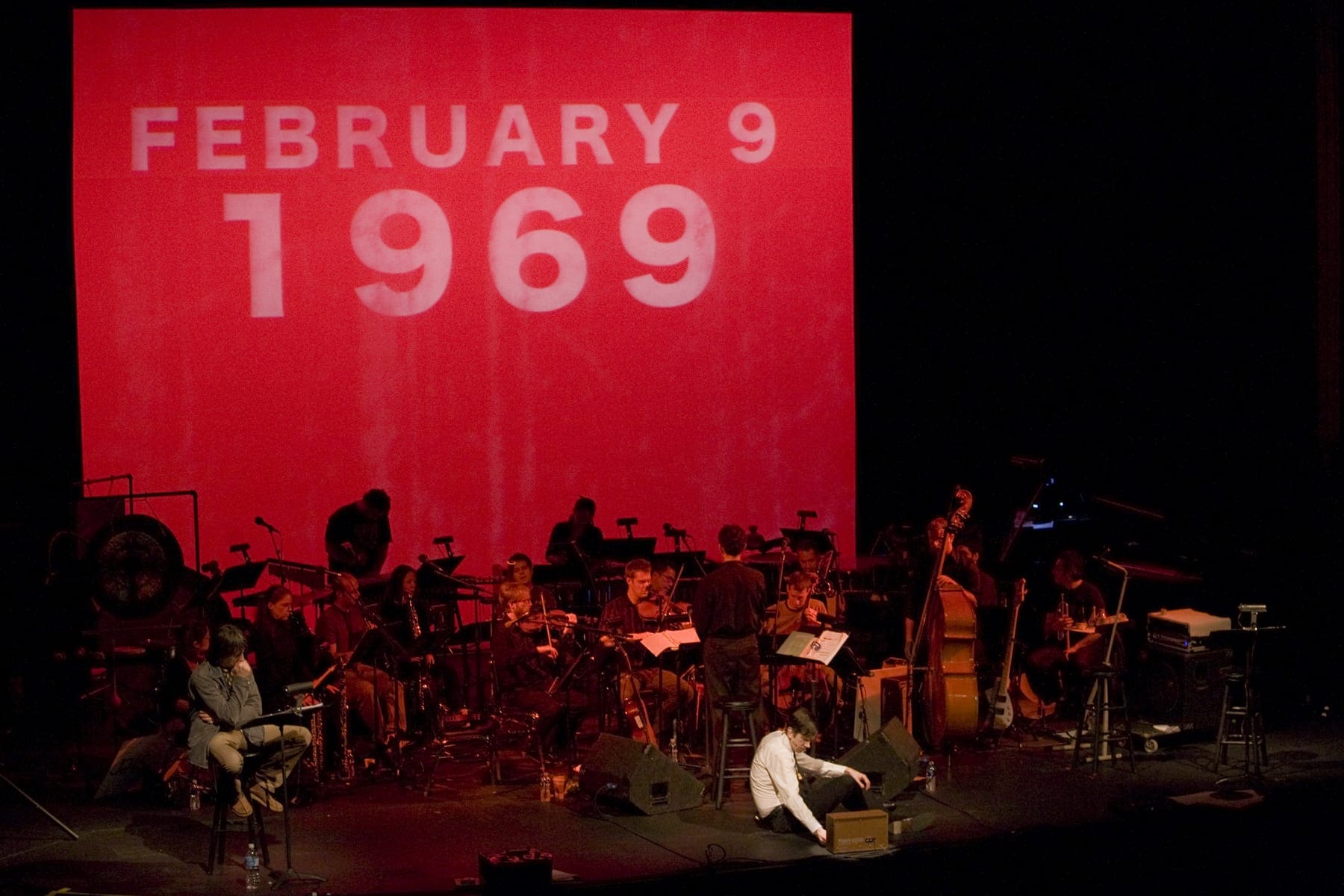

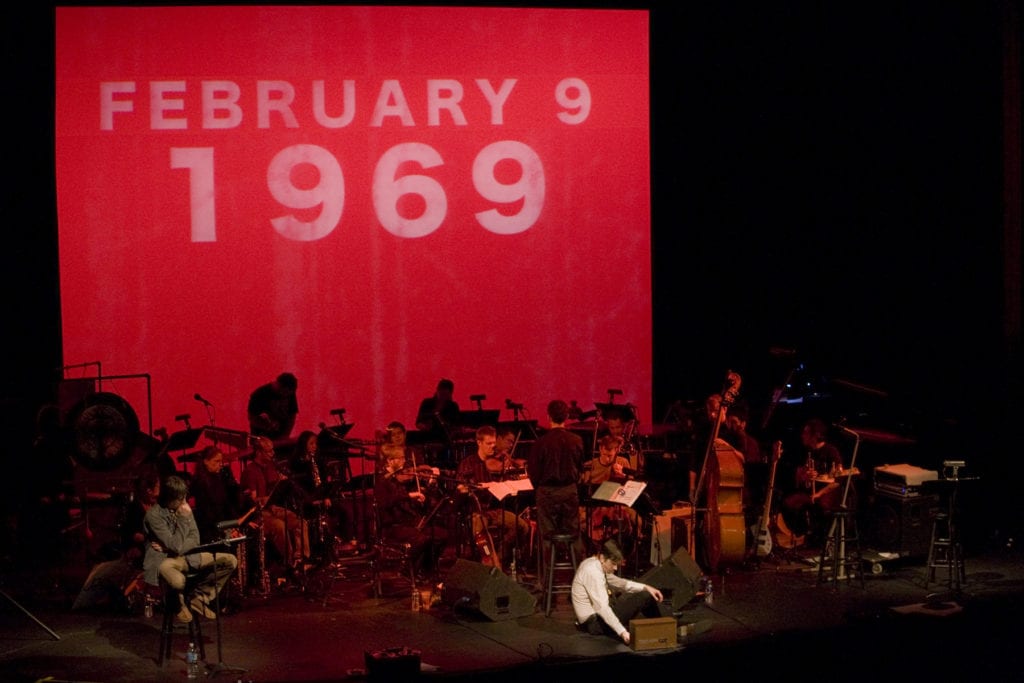

“Nonchalantly virtuosic” and “Überhip” (New York Magazine, Entertainment Weekly), the 20-member contemporary classical powerhouse ensemble Alarm Will Sound descended on Durham for a weeklong residency in Spring 2009, culminating in the world premiere of composer Alan Pierson’s provocative and mutidisciplinary new work, 1969.

For the premiere performance on February 13, 2009 at Reynolds Industries Theater, the fearless classicists revisited a moment when politics, music, and protest converged. 1969 features bags of broken glass, memorial songs to MLK and RFK, and arrangements by Stockhausen, Stravinsky, Berio, and, magically, the Beatles (“Revolution 9”).

[foogallery id=”10342″]

The concept that became 1969 started out as something quite different. While brainstorming repertoire for an orchestral program, I noticed that Strauss’s Four Last Songs and Messiaen’s Turangalila Symphony were both composed in 1949. It seemed remarkable that two composers of apparently different eras with such divergent aesthetic outlooks were both writing these seminal works in Europe after World War II, and I wondered where else in history one could find such interesting confluences of musical thought and world events.

A little Wikipedia research quickly turned up 1969 as a promising candidate for a rich concert about a single year: 1969 saw the moon landing, the Nixon inauguration, the Stonewall riots, Woodstock, the final Star Trek episode, and the first Walmart. And there was more than enough beautiful and significant music from the year to make a terrific concert: Ligeti’s Chamber Concerto, Glass’s Music in Similar Motion, Shostakovich’s 14th Symphony, Cardew’s Scratch Orchestra, Reich’s Pulse Music, Stravinsky’s Hugo Wolf settings, Meredith Monk’s Juice, and Laurie Anderson’s symphony for car horns, amongst many others. I’d still love to hear a concert of all of those wonderful works from 1969; however, not a single one is included in tonight’s program.

Early on in my research, I stumbled on an anecdote that moved the project in an entirely different direction: Michael Kurtz tells of a meeting that had been set up to plan a joint concert between Stockhausen and the Beatles. The notion that the period’s most famous rock group would come together with one of its most powerful avant-garde composers was compelling. But there was little information about the meeting, and I received no response to my emails to the author asking for details. Curious and frustrated by the dearth of concrete information, I contacted Stockhausen’s assistant to see if I could ask the composer himself a few questions, but she wanted me to do my homework and instead emailed me a list of books I needed to read before talking directly with Stockhausen — he died before I finished them.

The more I learned about the year 1969, the more the Stockhausen-Beatles meeting seemed to resonate with the ideas and spirit of the time. And the lack of information about the meeting only made it more tantalizing. It was Ara Guzelimian at Carnegie Hall who first suggested that, rather than a catalogue of events and music from the whole year, 1969 might focus on this single, provocative tale. (He also argued that — as an homage to the famous naked scene in 1969’s Broadway sensation, Oh! Calcutta! — Alarm Will Sound should perform Cardew’s Scratch Orchestra nude in Carnegie Hall. We haven’t pursued this idea.)

And so the Stockhausen-Beatles meeting became the focal point of 1969. To tell its story, I imagined a unique multimedia piece that juxtaposed fragments of music, images and video from the period, and the artists’ own words — much of which have never been published. The format was inspired by the music that these composers were writing: collage was current in 1969, and most of the pieces at the center of our story — Stockhausen Hymnen, Lennon/Ono Unfinished Music, Bernstein Mass, Berio Sinfonia, and Lennon/McCartney Revolution 9 — shocked their first listeners by juxtaposing bits of disparate material in wholly original sorts of collages. This is not a conventional concert. Only one of the works is played in its entirety during the performance. But despite this — perhaps because of it — I want to share some information about the works that are most central to 1969.

— Alan Pierson

Duke Students & Employees save more!