Sönke Johnsen, Professor of Biology at Duke, is an artist at heart. The obvious sign is his specialty in visual ecology, with a special focus on marine life at its most fluorescent and ghostly. But the connection goes much deeper than that.

“To be blunt,” Johnsen says, “art totally motivates me as a scientist. Science, for me, is the tools I use to answer the questions, but the spirit behind the work is artistic.” This approach reflects a life that started with a deep absorption in the arts, without a thought for biology until after college.

Johnsen grew up in Pittsburgh. “My dad is a physicist,” he says, “but he’s also an extremely good photographer and he had a whole darkroom setup in our attic. He was very good with his hands, too, and built really nice, very artistic furniture.”

Following his father’s lead, Johnsen did a lot of photography and learned how to use the darkroom, but his mother was a big influence, too. “Before she went back to medical school, she spent much of her time throwing pots, painting pictures, and making clothes, all the while encouraging my brother and me to do the same. So in high school, besides the photography, I was also drawing a lot, and I was always building things—musical instruments, things of that sort.”

Starting college at Swarthmore, Johnsen fully expected to be a physicist like his father. “But I bailed on it pretty early on and did a weird sort of double major in math and art, except that I didn’t like the art history part, so they never gave me the official art major.”

He also threw himself (literally!) into dance. It started with a folk dance class he took to meet the physical education requirement. “I very quickly got interested in modern and jazz, and then just totally fell in love with it,” Johnsen says. “The problem was it was beating my body to death, breaking all these little bones in my feet and toes. It was really rough, but I really did love it.”

“I sort of lived between the art studio and the dance studio. And I was also designing and building sets for various plays,” Johnsen says, all the while dutifully cranking out the problem sets for his math classes.

“When I finished college, I just lived the life. I had all these different, random jobs, mostly to support the other things I really wanted to do—dancing, and writing stories, and building things, and doing weird performance art pieces.”

“I taught dance to little kids for a while, which I really liked. And then I taught kindergarten, taught first grade, and then, believe it or not, ran a daycare center.”

Johnsen also did freelance carpentry, and that’s what ultimately brought his day-gig period to an end. “The person we were working for went insane and thought we were trying to kill her, so we made a run for it. And as we were driving away, we decided we needed to have real jobs where we could control our destinies.”

Hear Sönke on WUNC’s The State of Things

Very much in the spirit of starting fresh, Johnsen picked biology, a discipline he had no experience with. “Never having taken a biology course,” he explains, “I just thought it might be kind of cool.”

His first step on the path was another day job, working in a university biology lab, and from there he found a graduate program that would take students who didn’t know any biology but did know math.

It wasn’t exactly love at first sight. “In the beginning,” Johnsen says, “I would just sit out on the lawn and draw pictures of the insects sitting out there with me. And then it started to hit me how beautiful the animals were.”

He remembers dropping in on his advisor to share the news. “This was after a year of being in his lab. Colleagues were making fun of him because of his student who just sat there and drew all the time. I think I told him, ‘I have a religious and spiritual feel about this, this is really good.’ And he just looked at me and said, ‘Well, that’s good!’”

Nature was an especially big revelation, Johnsen suggests, because he had so little contact with it growing up. “Especially at that time, Pittsburgh was a horrible filthy pit—the most anti-natural place in the world. The natural world was this new thing to me, and all of a sudden I could see a lot of the things that drew me to art in it.”

It’s a deeply beautiful system in which appearance and behavior—form and function—have been shaped by the meticulous logic of evolution and a few basic drives. “Animals need water, they need food, they need sex, and so on,” Johnsen says, “but every animal co-opts the world in its own special way. Like, I remember learning about sand dollars—all these little brainless animals standing on their sides to catch the flow just right and grab little bits of food out of it. It was neat!”

“It’s just so wonderfully balanced—such a weird combination of awe inspiring and at other times, just really venal, and stupid, and selfish. Anything involving mating systems is hysterical.”

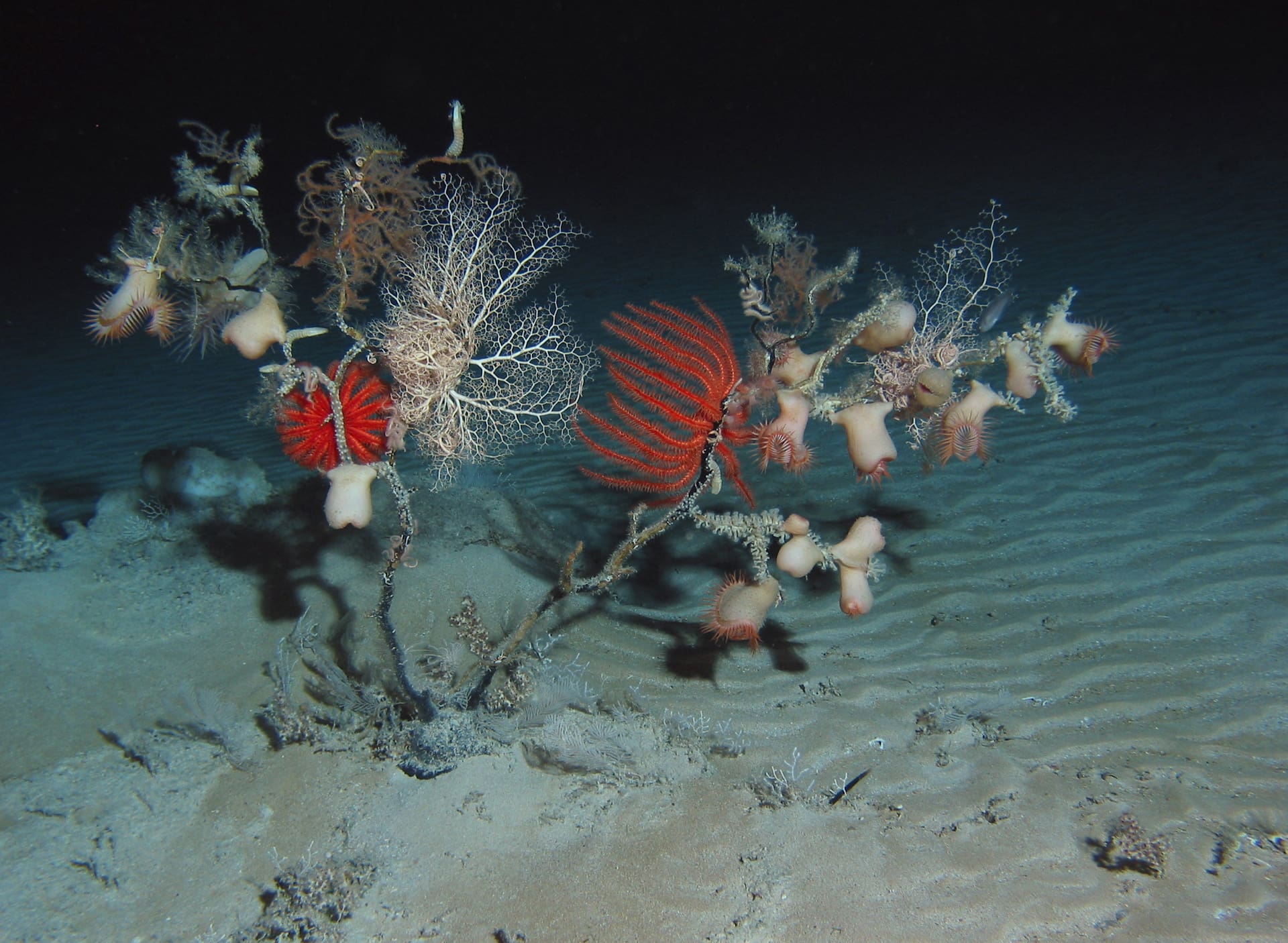

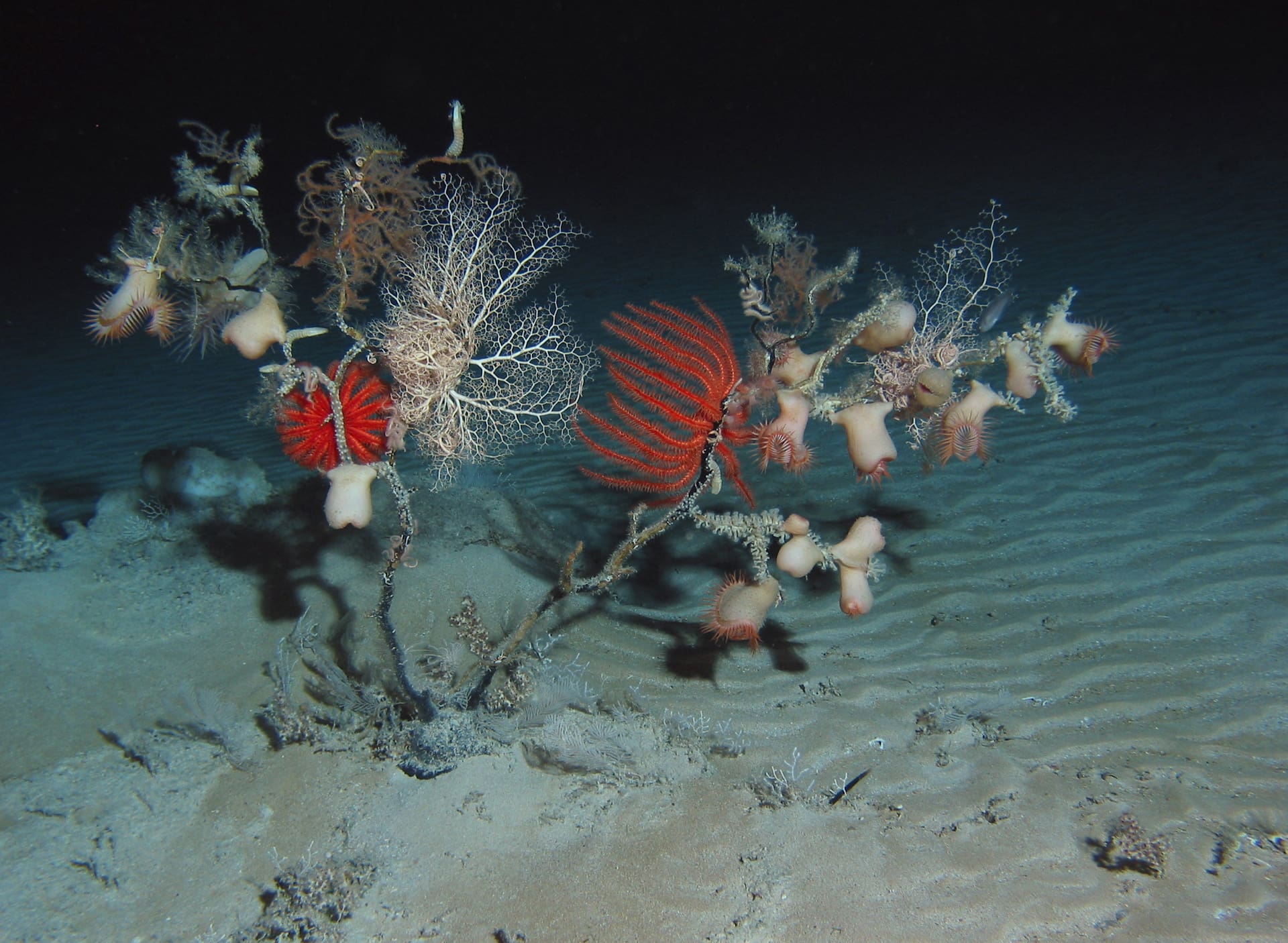

“My interest in color and light grew out of my passion for the arts,” Johnsen says. But it’s not just the stunning visuals that make his studies of marine animals artistic, it’s the way they’re shaped by the rigors of an environment where seeing but not being seen are matters of life and death. Like a royal child in a portrait by Goya, the fascination of Johnsen’s subjects is the truths about their world that are stamped on their faces and forms.

“Like any practicing biologist, I’m rigorous and I follow the rules of the craft,” Johnsen says, “but the way I decide what’s interesting, what’s exciting, what’s worth looking into is entirely about the aesthetic appreciation of it. Sometimes the work turns out to be useful, or ties into some big area of biology. Sometimes I’ll choose to work on some strange little thing just because I like it. It’s like sitting down and making some pretty little piece of jewelry that only one person ever gets to wear. I’m lucky that I’ve gotten to a position in my life where I can just say that.”