Anthony Patterson, the young painter currently in residence at the Power Plant Gallery, is a child of Durham with both art and activism in his blood. His grandfather played a leading role in the lawsuit that spared the Crest Street neighborhood where Patterson grew up—a historically black enclave just blocks from Duke Hospital—from the obliteration inflicted by the Durham Freeway on Hayti and other African American neighborhoods. Patterson’s father is an artist and his sister is an interior designer. For high school, he went to the J.D. Clement Early College program at North Carolina Central University. He went on to graduate from UNC Greensboro with a BFA in painting in 2017.

During his #PPGArtists residency, Patterson is starting a project he calls PIGEONHOLED—a documentary project that involves recorded interviews and paintings. By mid-August, paintings of his first two subjects were hanging in his work area, with short audio clips from Patterson’s interviews with them playing in a loop.

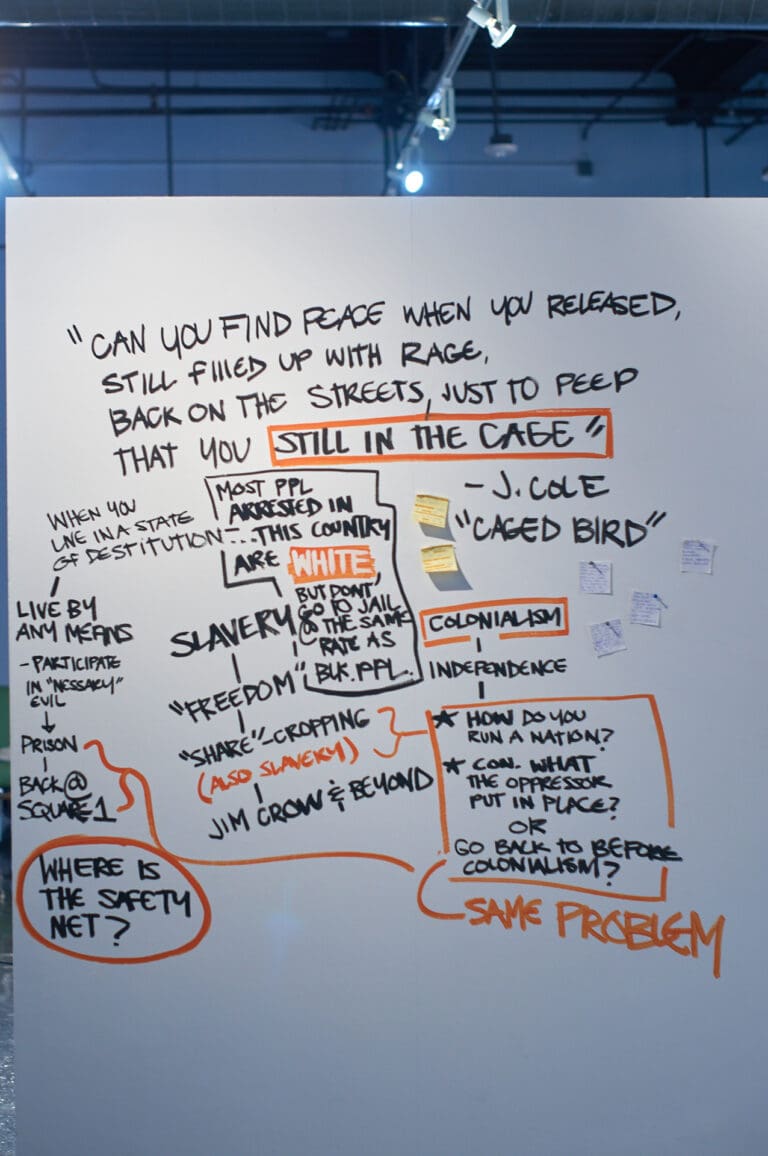

Four bold lines written at the top of a wall facing Patterson’s worktable serve as the project’s epigraph. They’re from “Caged Bird,” a song by J. Cole.

Can you find peace when you released,

Still filled up with rage,

Back on the streets, just to peep

that you still in the cage?

Patterson’s plan for the project is to start with friends and family and then find men outside of his circle, to get a range of experiences and perspectives. His first subject is one of his best friends from childhood. “He got locked up at 17, did five years, and was on the straight and narrow for a while,” Patterson says, “but now he’s dealing with a new situation.”

Subject number two, an older cousin, “is kind of on the opposite end of the spectrum than my friend,” Patterson says. “His life passion is golf—he’s so good he can balance golf balls at the end of a club—so when he got out of prison he was able to grow himself, go to school and learn about golf management.”

This is a good outcome but it’s also more the exception than the rule. The golfing cousin had a skill and a passion that he could build on. He also had the good fortune of finding somebody willing to take a chance on him after many others, seeing his criminal record, turned him away without a second thought. The criminal record is the most tangible way the prison system keeps people caged even after supposedly “freeing” them. “It’s like a scarlet letter,” Patterson says, “big and bold—you can’t get around it.”

A line of small square paintings pinned up like mugshots on the back wall of the studio is Patterson’s Any Black Man series, which prepared the ground for PIGEONHOLED. The work reflects Patterson’s experience crashing an art reception along with four fellow students dressed in orange prison jumpsuits. Everyone who witnessed the event knew that it was part of Sherrill Roland’s Jumpsuit Project, but some of the reactions from within Patterson’s academic circle were still eye-opening.

Like most of his fellow students, Patterson first encountered Sherrill Roland as a black man walking around campus in an prison jumpsuit—his way of publicly processing 10 months spent in prison based on false charges. “It was very shocking for most people at first,” Patterson says, “and then once people were more accustomed to what he was doing, it became something more interesting to talk about.”

Roland’s appearance was life changing for Patterson, who was frustrated by the lack of faculty of color at his school and “the whitewashing of art in general.” Through the example of his carefully staged intervention and also through his friendship, Roland brought Patterson’s discontent into productive focus.

Patterson’s artistic vision and ambition is not bound by any one issue or by his identity, though, as he shows in this answer to an emailed question about his influences.

My life experiences, thoughts, and questions motivate me to create. I investigate culture. Whether it’s how a song relates to my life, or how that same song can be interpreted through America’s current political landscape. I find myself asking questions that begin with “What if”, “How come”, and “Why”. My approach to art is somewhat scholarly. I search through historical archives, read, and record conversations with my peers. I reconfigure the source material until I can paint a story with a unique twist. Aesthetically, I am a figurative painter. My figures struggle within tight, uncompromising settings. Abstraction creeps into my work as I intuitively make marks on the surface. Sometimes those marks personify themselves within the painted narrative. Some of my artistic influences are Francisco Goya, Titus Kaphar, Jerome Lagarrigue, Ryan Hewett, and specifically for this project, Francis Bacon. These artists give me the artistic license to be raw, provocative, and colorful with the topics I address in my work.

The obvious sign of Bacon’s importance is a well-thumbed catalog of his paintings on Patterson’s worktable, Bacon’s way of putting boxes around his subjects is the influence most visible in Patterson’s work. Bacon wrote about this technique as a purely formal device to separate the figures from the background, but Patterson is skeptical. “He was a gay man in England whose family disowned him, and a lot of his lovers were his subjects,” Patterson says. “There’s no way those boxes are just a spatial device.”

The basic idea the #PPGArtists fellowship is for the artist to work in the studio, and to invite the public into the process—a show of finished work is not the priority. Since reading and study are essential to Patterson’s process, he has some key books on hand, like Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, as well as sketchbooks from his college days. It’s material he’s eager to process and discuss.

Patterson’s residency ends on Saturday, September 1, after a reception on Thursday, August 29, 6-9pm (artist’s talk at 6:30pm).

Follow him on Instagram: @signedbyap!