This is the first in a series of profiles of faculty at Duke whose life and work are shaped by a background in the arts—even though their primary work now lies beyond the arts.

The faculty we will profile have taken a circuitous path through the arts to other intellectual preoccupations that reward intense focus and require extensive study. These artist-scholars represent a population that can be found on any college campus—though their stories and unique training often go uncelebrated. While their pathways are winding, the connecting thread between their experiences is clear: the intense, sustained effort that it takes to develop a high level of artistic skill does things to a person’s brain. These profiles show how the passionate pursuit of art can be a source of broad intellectual strength and insight.—Scott Lindroth, Vice Provost for the Arts

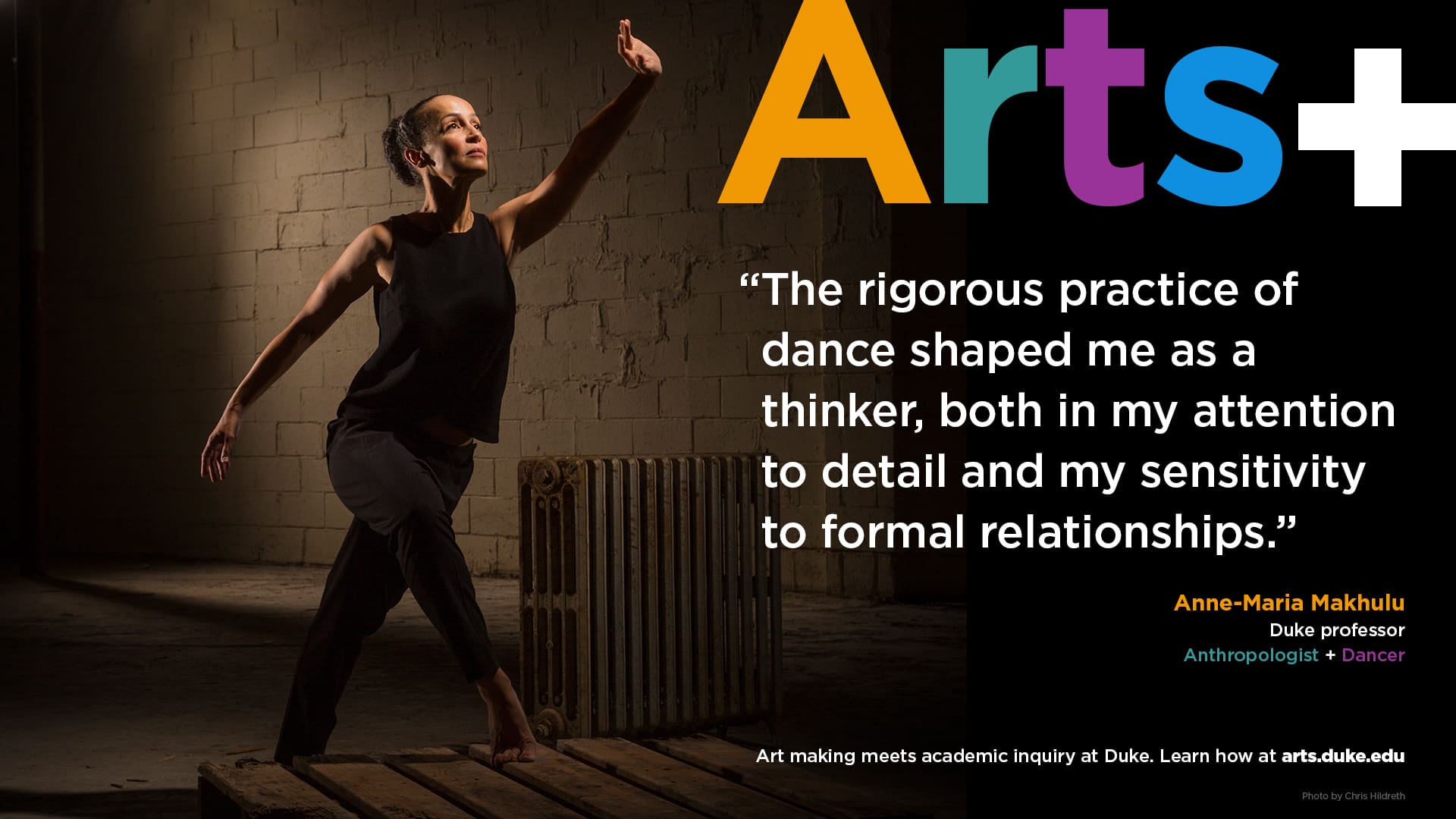

“Like a lot of little girls, I wanted to be a ballet dancer,” says Anne-Maria Makhulu, Associate Professor of Cultural Anthropology and African and African American Studies at Duke. A scholar using the tools of anthropology and political economy to understand contemporary African city life, she started dance classes in London at age four and continued them in Geneva when her family moved a few years later. At 16, she went on to a performing arts boarding school in the U.K. and then moved to New York City to study at the school founded by Alvin Ailey.

That’s a very conventional narrative, but it leaves out the four crucial years, starting at age 12, she was living in Gaborone, Botswana. Her father, Walter Paul Khotso Makhulu, an Anglican cleric—first appointed Bishop of Botswana and then two years later Archbishop of Central Africa—would go on to establish an underground railroad to help opponents of apartheid escape from South Africa.

There were no ballet teachers in Gaborone at the time. “Fortunately, I fell in with another expatriate family that was also interested in the performing arts,” Makhulu explains. “The parents—the mother, really—had been quite ingenious and self-motivated and convinced a ballet teacher to drive up from Mafikeng just across the border every Friday to teach.”

Makhulu was also able to take tap, modern, and music lessons—paid for in part by the work she did demonstrating for the classes for the little kids. She and fellow students put on musicals like Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat and Pippin. Still, when she went to boarding school in West Sussex at age 16, she found herself competing with girls who had trained continuously, making her acutely aware of what she had missed.

“I had one really extraordinary teacher who saw in me a potential that would not be realized, partly because of those four years in Botswana, but also because there was still incredible racism within British ballet companies. The same was true of the US, but Britain had no Dance Theater of Harlem, nor an Alvin Ailey.”

A teacher helped arrange a scholarship for Makhulu at the Alvin Ailey American Dance Center, where she spent about two years learning forms of classical and modern technique more suited to her body type and abilities. She blossomed as a dancer—but struggled to translate that into professional success.

After a brief stint with a company in Memphis and a few years struggling to make it in New York, she enrolled in the School of General Studies at Columbia University—a program favored by dancers facing the need to reinvent themselves. She was one of six dancers—a group that ranged in age from their late 20s to mid 30s—who graduated with honors in 1994.

She notes that, as dancers, routine and repetition were second nature. “We didn’t really see it as a sacrifice to sit there and read and read and read and write and write and write—you know, in a way, rehearse,” she says.

“Every day that you go to a dance class is a slightly different day. There’s no sense that repetition is the same. You attempt the same, but you might not be able to achieve it. You also have to hone your technique of writing and you will never ever be able to stop rehearsing, because if you do, you will lose your edge. Writing is a practice, just like dancing is a practice.”

“You also have to hone your technique of writing and you will never ever be able to stop rehearsing, because if you do, you will lose your edge. Writing is a practice, just like dancing is a practice.”—Anne-Maria Makhulu

There is a related practice, essential for academics, in reading. “I’m rereading a section of volume one of Das Kapital for my lecture class on Thursday,” Makhulu says. “Reading is unstable, every reading is different from the last, but it requires a certain kind of discipline to hold the attention. Even though I’ve read those passages, it could easily be 50 times, something I’ve seen will inspire a rereading that’s slightly distinct.” Dancers have to pay exquisite attention to minute adjustments to the body, particularly at the barre.

At a conceptual level, Makhulu sees deep ties between her early immersion in the formalism of dance and her fascination with ethnography and social theory. “The formalist in me who loves ballet and loves New York City Ballet most especially, and the most formalistic of the choreography of the Alvin Ailey Company, is also the person who loves social theory,” she says.

Much of her work focuses on the social organization of the informal settlements of black South Africans. Her book, Making Freedom: Apartheid, Squatter Politics, and the Struggle for Home, is based on fieldwork in Cape Town. The study leads her to reflect on the persistence of a system produced by apartheid: “Why it is that despite the transition to democracy, despite attempts at urban reconstruction and development, cities like Cape Town have larger informal settlement populations than they ever had historically?” In all the messy details of improvised lives, the formalist sees a broad choreography of “space and geography and power.”

“The rigorous practice of dance shaped me as a thinker,” Makhulu says, “both in my attention to detail and my sensitivity to formal relationships. But don’t forget, there’s also pleasure!” The feeling of a perfectly executed turn, and the beauty of bodies arranged and rearranged just so, are powerful motivations to keep moving and stay engaged.